Test Case Design in Software Testing

- 19 Jan 2026 06:22

- Updated: 14 Jan 2026

- 40 Views

- 12 min.

Understanding the Core of Software Testing

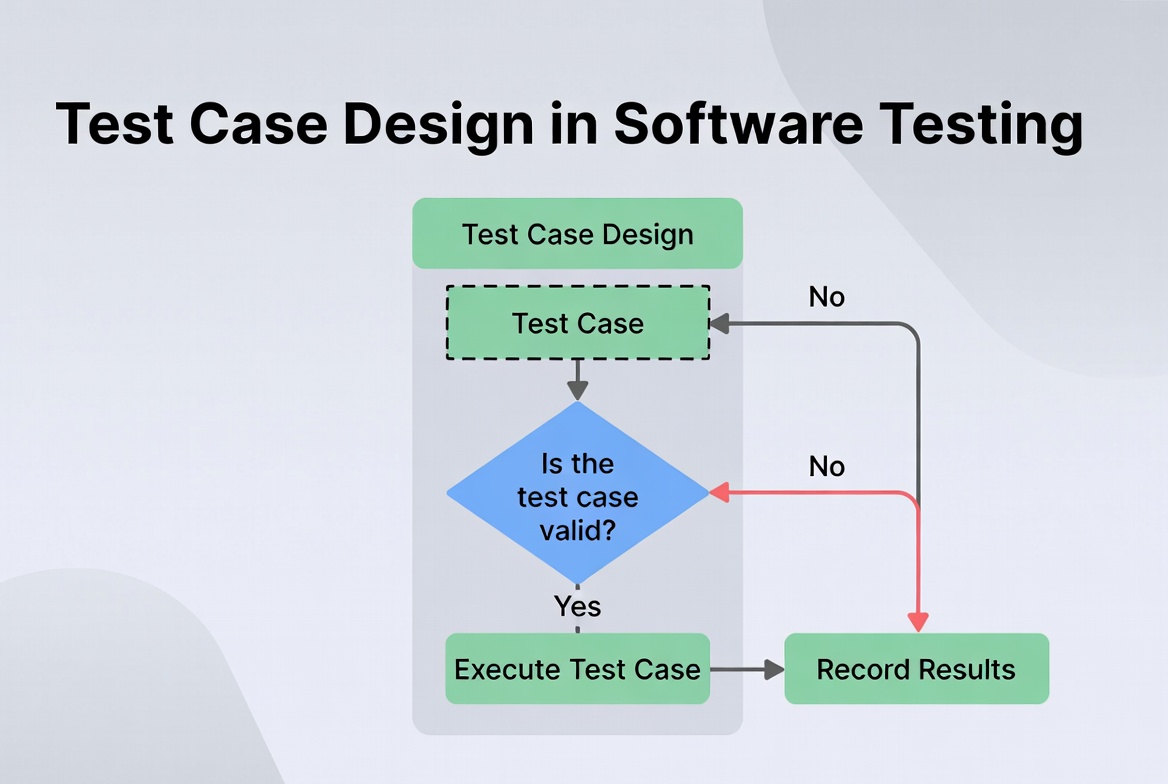

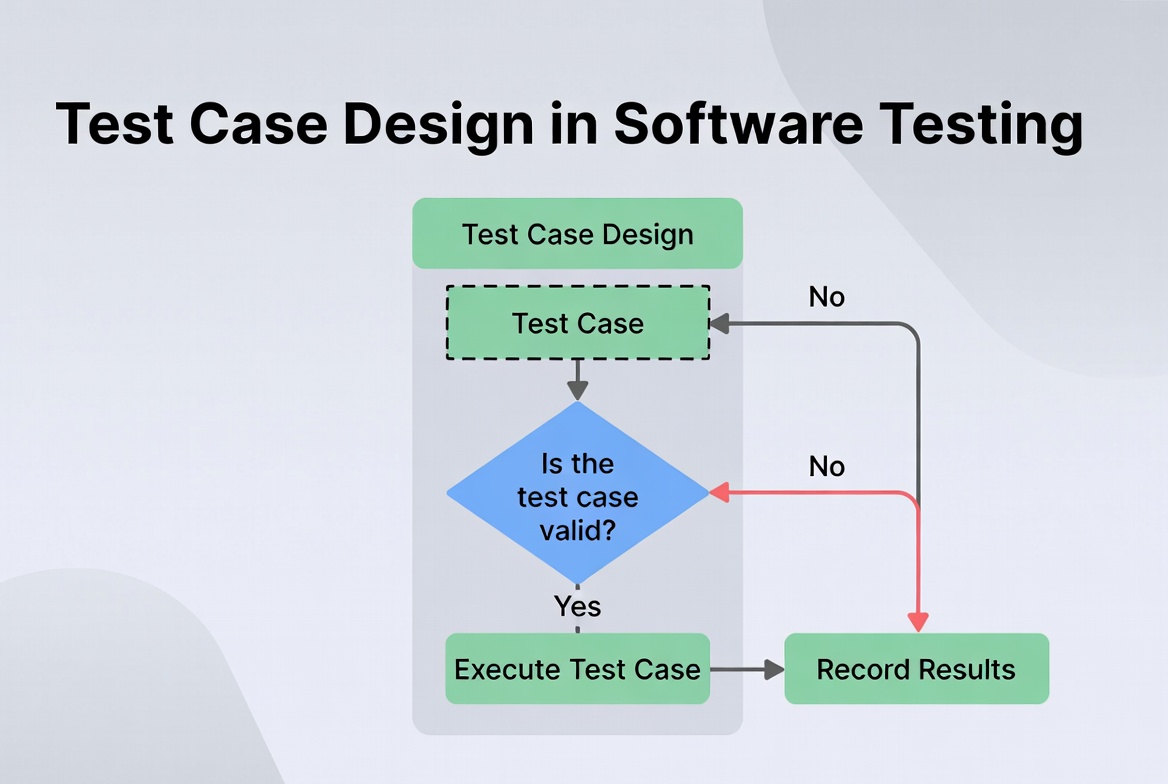

Software testing is a systematic process crucial for delivering reliable and high-quality applications. At its heart lies test case design, a structured methodology for creating scenarios that validate whether software functions as intended. A well-designed test case acts as a blueprint, guiding testers through precise steps to verify specific functionalities, identify defects, and ensure the software meets both technical specifications and user expectations. How do you transform vague requirements into actionable validation points? The answer lies in mastering the art and science of test case design techniques, which provide the framework for building a robust, efficient, and effective testing strategy. This discipline moves testing from an ad-hoc activity to a measurable, repeatable, and controlled engineering practice, directly impacting the product’s stability and user satisfaction.

- Understanding the Core of Software Testing

- What is a Test Case? Definition and Key Elements

- The Strategic Importance of Test Case Design Techniques

- Black-Box Test Design Techniques: Focusing on External Behavior

- White-Box Test Design Techniques: Analyzing Internal Structure

- Experience-Based and Hybrid Test Design Techniques

- Table: Comparison of Key Test Case Design Techniques

- Best Practices for Effective Test Case Design and Implementation

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is a Test Case? Definition and Key Elements

A test case is a detailed set of conditions, steps, data inputs, and expected outcomes used to verify a particular feature or function of a software application. It is the fundamental unit of testing, transforming abstract requirements into concrete, executable validations. Think of it as a recipe for checking one specific behavior of the system. A comprehensive test case is more than just a step-by-step guide; it is a self-contained artifact that includes several critical structural elements. The Test Case ID provides a unique identifier for tracking. The Test Objective clearly states what functionality is being verified and why. Preconditions outline the system state required before execution begins, such as a user being logged in. Test Steps offer a sequential, unambiguous list of actions for the tester to perform. Test Data specifies the exact inputs to be used, covering both valid and invalid values. Expected Results define the precise outcome each step should produce, serving as the benchmark for pass/fail determination. Finally, Post Conditions describe the state the system should be left in after test execution, ensuring test isolation and repeatability.

The Strategic Importance of Test Case Design Techniques

Why can’t testers simply explore the application randomly? While exploratory testing has value, systematic test case design techniques are essential for achieving reliable test coverage and maximizing defect detection within constrained time and resources. These techniques provide a methodological foundation that guides testers in selecting the most effective test conditions and data. They answer the critical question: “Out of the nearly infinite number of possible tests, which ones are most important to execute?” By applying these techniques, testing teams can move from testing “everything” (which is impossible) to testing “smart.” They help ensure that tests are derived from requirements logically, not just intuitively. This systematic approach reduces redundancy, uncovers specific classes of defects (like boundary errors or logic faults), and provides a measurable way to assess how much of the application’s logic or functionality has been exercised. Ultimately, these techniques transform testing from a potentially chaotic activity into a disciplined engineering task.

Black-Box Test Design Techniques: Focusing on External Behavior

Black-box testing techniques are fundamental methods where the tester examines the software’s functionality without knowledge of its internal code structure. The tester views the software as a “black box,” focusing solely on inputs and expected outputs as defined by requirements. This approach aligns closely with the user’s perspective. Boundary Value Analysis (BVA) is a powerful technique based on the principle that defects frequently cluster at the boundaries of input ranges. Instead of testing all values, BVA targets the values at the edges: the minimum, just above minimum, a nominal value, just below maximum, and the maximum. For example, if a field accepts ages 18 to 65, test values would be 17, 18, 19, 64, 65, and 66. Equivalence Partitioning (EP) reduces the number of test cases by grouping inputs that are expected to be processed identically by the system. One value from each partition is sufficient to represent the entire group. In the age example, valid (18-65), invalid-low (<18), and invalid-high (>65) are three partitions. Decision Table Testing is ideal for business logic with multiple conditions leading to different actions. It creates a matrix listing all possible combinations of conditions and their corresponding outcomes, ensuring complex rule-based logic is thoroughly verified. State Transition Testing models the system as a finite set of states and triggers that cause transitions between them. It is perfect for testing workflows, like a login process (states: initial, username entered, authenticated, locked) or an order status (pending, paid, shipped). Pairwise Testing is an efficient combinatorial technique that tests all possible discrete combinations of each pair of input parameters, catching most interaction defects with a fraction of the test cases needed for exhaustive combination testing.

White-Box Test Design Techniques: Analyzing Internal Structure

White-box testing techniques require knowledge of the application’s internal logic, code paths, and structures. These techniques are used to ensure that the internal workings of the software are sound. Statement Coverage, the most basic form, aims to execute every line of source code at least once. While it ensures no code is “dead,” it’s a relatively weak measure. Decision Coverage (Branch Coverage) strengthens this by requiring that every possible branch (e.g., every if and case statement) is taken at least once, ensuring both true and false outcomes are tested. Condition Coverage goes further, ensuring each Boolean sub-expression within a decision is evaluated to both true and false. Modified Condition/Decision Coverage (MC/DC), a stricter criterion often used in safety-critical systems, requires each condition to independently affect the decision outcome. Path Testing is one of the most thorough techniques, aiming to execute every possible logical path through a given part of the program. While exhaustive path testing is usually infeasible for complex modules, focusing on critical paths and using techniques like basis path testing (using cyclomatic complexity) provides a practical and robust approach. Data Flow Testing focuses on the points where variables are defined (“def”) and used (“use”), creating test cases to cover specific definition-use paths and catching anomalies like using a variable before it’s defined.

Experience-Based and Hybrid Test Design Techniques

Not all testing wisdom comes from formal models. Experience-based techniques leverage a tester’s skill, intuition, and knowledge of the system and common failure modes. Error Guessing relies on the tester’s experience to hypothesize where defects might be lurking—areas like empty form submissions, extreme input values, or interrupting processes. Exploratory Testing, while sometimes seen as unstructured, is a disciplined approach of simultaneous learning, test design, and execution. The tester designs and executes tests in real-time based on insights gained from previous results, making it exceptionally effective for uncovering usability issues and complex, unanticipated bugs that scripted tests may miss. In practice, the most effective testing strategies are hybrid, combining the rigor of black-box and white-box techniques with the adaptive, creative power of experience-based testing. For instance, one might use equivalence partitioning to define core test data, decision tables to verify business rules, and then employ exploratory sessions to investigate the user interface and integration points that are difficult to capture in scripts.

Table: Comparison of Key Test Case Design Techniques

| Technique | Category | Primary Focus | Best Used For | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boundary Value Analysis (BVA) | Black-Box | Input domain boundaries | Numeric ranges, limit fields | Efficiently finds off-by-one and edge-case errors. |

| Equivalence Partitioning (EP) | Black-Box | Groups of similar inputs | Data validation, input forms | Dramatically reduces number of test cases. |

| Decision Table Testing | Black-Box | Business rules & logic combinations | Complex conditional logic (e.g., discounts, approvals). | Ensures all rule combinations are considered. |

| State Transition Testing | Black-Box | System states & transitions | Workflows, wizards, session management (e.g., login). | Excellent for testing sequences and invalid transitions. |

| Statement Coverage | White-Box | Executing each line of code | Initial unit-level validation | Ensures no unreachable “dead” code. |

| Decision/Branch Coverage | White-Box | Executing each decision branch | Unit and integration testing of logic. | Stronger than statement coverage; tests both outcomes of conditions. |

| Path Testing | White-Box | Executing independent paths | Critical, high-risk code modules. | Very thorough; uncovers complex logical errors. |

| Exploratory Testing | Experience-Based | Learning & adaptive investigation | New features, UX, complex integrated systems. | Finds unexpected bugs and usability issues missed by scripts. |

Best Practices for Effective Test Case Design and Implementation

Creating test cases is an art, but implementing them effectively is an engineering discipline. First, maintain traceability by linking each test case directly to a specific requirement or user story. This ensures all features are covered and allows impact analysis when requirements change. Second, prioritize ruthlessly. Use risk-based analysis to focus design efforts on high-impact, high-risk areas of the application. Not all test cases are equal. Third, design for maintainability. Write clear, concise, and modular test cases. Use a consistent naming convention and structure. Avoid hard-coded data where possible; use variables or data files to make updates easier. Fourth, balance positive and negative testing. While verifying expected behavior is crucial, designing test cases for invalid, unexpected, and malicious inputs often uncovers more severe defects. Fifth, promote reusability. Design test steps and components that can be assembled into larger test scenarios, reducing duplication and effort. Finally, review and refine. Peer reviews of test cases are as important as code reviews. They improve clarity, uncover missed scenarios, and share knowledge across the team.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the difference between a test case and a test scenario?

A test case is a low-level, detailed set of specific steps, data, and expected results to verify a single condition. A test scenario is a high-level description of a user’s objective or a storyline to be tested (e.g., “User successfully places an order”). A single scenario may require multiple detailed test cases to be fully validated (e.g., test cases for adding items, applying a coupon, selecting shipping, and completing payment).

How do I choose the right test design technique for a feature?

The choice depends on the feature’s nature and the testing objective. For input validation, use BVA and EP. For complex business rules, use Decision Tables. For workflows and navigation, use State Transition. To ensure code logic is sound, apply white-box techniques like decision coverage. For new or poorly understood areas, start with Exploratory Testing to inform more formal test case design later. Often, a combination is best.

Is 100% test coverage a realistic or useful goal?

100% code coverage (like statement or branch coverage) is a measurable but often misleading metric. It is possible to achieve high coverage while missing critical functional bugs. The goal should be effective coverage of requirements, user journeys, and risk areas, not a coverage percentage alone. Focus on designing meaningful test cases for important functionalities rather than chasing a perfect coverage score, which can be costly and offer diminishing returns.

How can test case design help with test automation?

Good test case design is the prerequisite for successful automation. Well-designed, modular, and repeatable manual test cases are the easiest to automate. Techniques like equivalence partitioning help create efficient, data-driven automated tests. A clear test case structure (preconditions, steps, expected results) maps directly to the structure of an automated test script. Investing in thoughtful design reduces maintenance costs and increases the stability of your automated test suite.

What role do test case design techniques play in Agile development?

In Agile, with its short cycles and evolving requirements, test case design techniques are crucial for speed and adaptability. Techniques like pairwise testing help create effective test suites quickly. Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) frameworks like Cucumber often use scenario outlines that are directly supported by equivalence partitioning. Lightweight decision tables can be built collaboratively with developers and product owners to clarify acceptance criteria. The focus shifts to designing “just enough” high-value tests for the current iteration, relying on techniques to ensure they are efficient and effective.

Keywords: test case design, software testing techniques, boundary value analysis, equivalence partitioning, decision table testing, white box testing, black box testing, test coverage, exploratory testing, test case examples

Disclaimer: The information provided in all articles, guides, and content on this platform is for general informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended as professional advice, whether medical, legal, financial, technical, or otherwise.

While we strive to provide accurate, up-to-date, and reliable information, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the content. The use of any information on this platform is solely at your own risk.

The content may contain links to external websites or references to third-party tools, services, or individuals. We do not endorse, guarantee, or assume responsibility for the accuracy, quality, or practices of these external resources.

Specific fields such as health, finance, law, and software development require qualified professional consultation. You should always seek the advice of a relevant licensed expert or official source before making any decisions or taking any action based on information found here.

Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any other agency, organization, employer, or company.

The techniques, examples, and strategies shared, particularly in areas like software testing, study methods, or career advice, are illustrative. Their effectiveness may vary based on individual circumstances, specific tools, or changing environments. We encourage critical thinking and independent verification of all information.

We reserve the right to modify, update, or remove any content at any time without prior notice.

Tags :